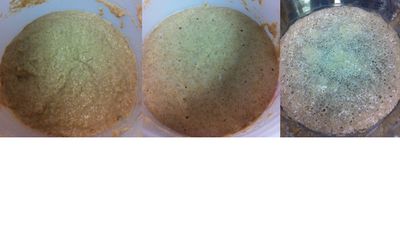

Three stages of my wheat starter. From left-right: just fed starter, fermenting starter, ready to feed again.

This is the second of a series of articles getting into detail about sourdough and bread baking. It all started with this post about what's in a sourdough culture and wraps up with a discussion of how bakers can control the flavour of their sourdough.

Part of the fun of bread baking is the how one can bake a huge variety of breads, each with its own distinct flavour, from a few simple ingredients. In the case of Sourdough baking, it can be as little as three ingredients: flour, water and salt.

In the last article, I talked about the difference between commercial yeast and a mature sourdough culture. Now I want to talk about the different components of flavour that exist in a sourdough culture, which the baker can control during the baking process.

So, how does the sourdough culture affect flavour? Well, it helps to think of your sourdough culture as a continually fermenting dough. And there's a lot going on during fermentation. At a microscopic level, once flour and water come into contact with each other, all hell breaks loose:

-

Enzymes which have been lying dormant in the flour wake up once they get wet. And they are cranky little fellas. They start attacking the starch molecules in the flour (the white bits in the centre of the wheat berry) and converting it to the simple sugar, glucose.

-

The baker's best friend, lactic acid bacteria, LOVE sugar. They convert the glucose into lactic acid. That's the hint of tang you get from buttermilk, yogurt, or a fine sourdough loaf.

-

Yeast cells also LOVE sugar. The little yeasties only want to do two things: eat glucose and divide. And they do both really fast -- eating the glucose, belching out carbon dioxide and dividing into new yeasties which eat more, belch more and divide more. (As an aside, it's the carbon dioxide that gets belched out by the yeast that makes bread rise. Gluten protien -- the bakers other best friend -- traps the gas inside the loaf, like air in a balloon, and the bread goes "up.")

It's mayhem in there! But for the first several hours, everyone is happy and healthy and making yeast babies. All good things must come to an end, however. If left long enough, like 8-12 hours, the starch in the flour gets used up and there's much less starch and sugar left and much more carbon dioxide (from the yeast.) That upsets the balance in the culture; starved for oxygen, the lactic acid bacteria start to fade away and a different type of fermentation begins. This "anaerobic" fermentation starts creating acetic acid. Instead of a light yogurty taste, the culture starts taking on a stronger, vinegary taste.

Taken to the extreme, all the starch is used up, the protein bonds break down and your starter begins to starve. At that point all that's really there for flavour is the vinegar. It's time for a feeding -- mixing in more flour and water so there is more starch for the enzymes and sugar for the yeasties and bacteria.

Of course, it would be nice if there was some yummy glucose left for us to eat too! People like sugar and besides, sugar caramalizes when baking which gives your bread a dark brown crust.

So there you have it! Flavour from the flour itself (wheat bran and other minerals taste yummy), lactic acid, acetic acid and glucose. We get to play with these four factors to create a range of flavours in our sourdough bread. But how exactly do we control the flavours, so our bread tastes the same every time? That's a great question -- and that's the topic for my next post. Stay tuned!

_